What we pay for when we pay for a gallon of gas

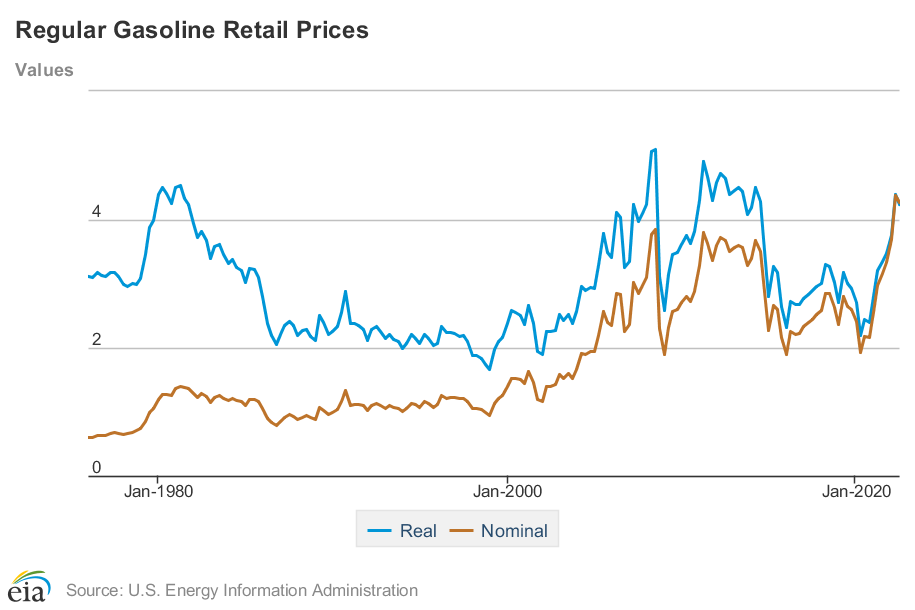

Gas prices are high — all-time highs nominally, and even approaching modern records adjusted for inflation.

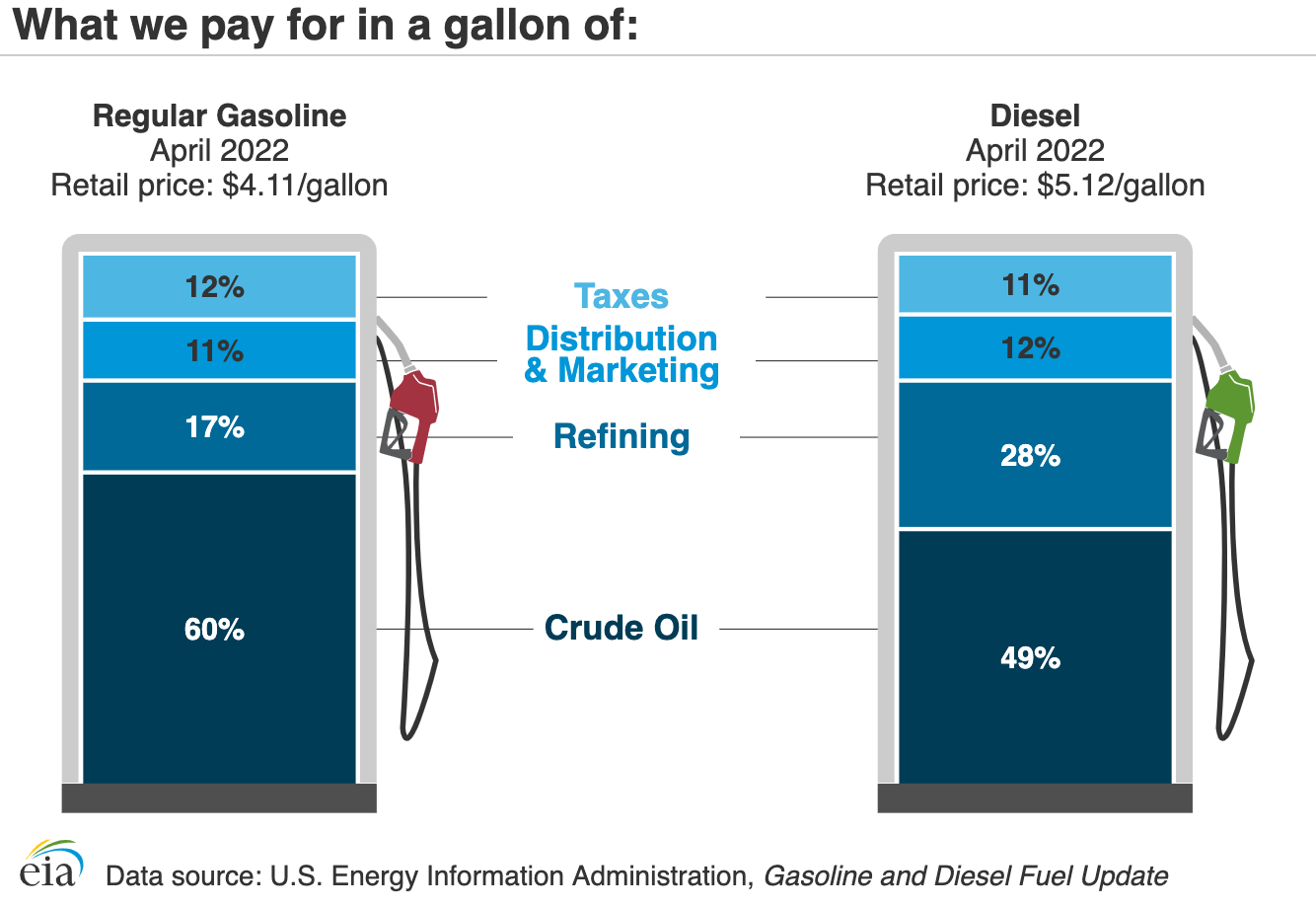

But what are you really paying for when you put $5-a-gallon gasoline in your (non-electric) vehicle? Crude oil, mostly. “A little more than half of the price of the gasoline relates to the price of crude oil,” University of Houston energy economist Ed Hirs tells WUSA9. “Now, of course, that percentage has been up a little bit here recently, as much as two-thirds of it.”

What’s in a gallon?

When you buy gas — or at least when you bought gas in April — 60 percent of your money goes toward crude oil, the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) says. The rest goes toward refining (17 percent), distribution and marketing (11 percent), and state and federal taxes (12 percent). So at $5 a gallon, $3 of your gas money goes to the company drilling or mining the crude oil. “On average, gas stations make about 5 cents per gallon of gas sold,” WUSA9 reports.

Those numbers are elastic, based on the cost of crude oil, price of gas, and other factors.

In May 2017, when the average price of gas was $2.39 a gallon, the Energy Department said crude oil made up only 48 percent of the price of a gallon of regular gas. In April 2020, oil was 52 percent of your gas dollar, and it was “just 25 percent in April 2020 — when the pandemic sapped demand for fuel, along with most other goods and commodities,” The New York Times reports. “For a brief moment in 2020, the cost of a barrel of oil fell below zero because storage tanks were full from the lack of demand.”

How much are gas taxes?

The federal gas tax is — and has been for a long time — 18.40 cents per gallon. Each state has its own tax rate, but the average of all total state gasoline taxes is 31.02 cents per gallon, the EIA says. Those taxes range from nearly 9 cents a gallon in Alaska to just over 77 cents a gallon in California and Pennsylvania.

What about refining?

You don’t pump crude oil into your car, and globally and domestically, refineries aren’t turning enough oil into gas to meet demand — President Biden noted pointedly in a letter to fuel makers last week that refiners reduced capacity by more than 800,000 barrels a day when the pandemic had drained demand. But it’s kind of complicated.

The U.S. is the world’s top producer of oil and processed petroleum products, a major exporter of crude, and the second-largest oil importer after China, the Times reports. “That’s partly because American refineries are often set up to process types of oil that are different from those produced in the United States. It would be expensive and difficult to reconfigure refineries to process more U.S. oil, which is why the United States is likely to continue importing large quantities even if it were to produce more domestically.”

At the same time, “in recent months, companies and commodities traders have shipped more U.S. gasoline and diesel to Latin America and other foreign markets, reaping higher prices than the fuel could fetch domestically,” The Wall Street Journal reports. “The jumps in fuel shipments abroad are further draining U.S. inventories that were already languishing at low levels after output cuts during the worst of the pandemic. Now, American oil-and-gas producers and refiners are struggling to keep up with resurgent demand.”

Will gas prices fall again?

Almost certainly, just as soon as global oil supply ramps up and/or demand falls enough. “The biggest single factor that drives changes in prices of gasoline is a change in the price of crude oil,” Mark Finley at Rice University tells WUSA9. “And the price of crude oil is not controlled by the companies. It’s set in a global marketplace as a result of global trends in demand and supply.”

Already, “fuel and crude oil are trading cheaper for delivery in the winter than today,” the Journal reports, providing a strong disincentive to fill storage tanks now. And oil and gas companies expect another oil price crash sometime in the future, making them hesitant to drill new wells or significantly ramp up gas production, MIT energy economist Christopher Knittel tells the Times.

Even though energy executives “see high prices today, they’re afraid that prices are gonna tank over the life of that well,” Knittel said. “They also have this expectation that electric vehicles are going to continue to grow, which means that 10 years from now, that oil well may not be earning profits. And so all of that is creating a disincentive to drill” or maintain, much less increase, refinery capacity.

Should prices fall again?

Not to be too much of a downer, but U.S. oil prices are probably artificially low, even at $5 a gallon. The Center for Investigative Reporting (CIR) tried to figure out how much gas really costs when you factor in pollution and resulting health issues. They decided the correct price for a gallon of gas is $15 a gallon — and that was in 2011, when the average national price of gas hovered between $3.09 and $3.91 a gallon.

Gas prices are high — all-time highs nominally, and even approaching modern records adjusted for inflation. But what are you really paying for when you put $5-a-gallon gasoline in your (non-electric) vehicle? Crude oil, mostly. “A little more than half of the price of the gasoline relates to the price of crude oil,” University of Houston…

Gas prices are high — all-time highs nominally, and even approaching modern records adjusted for inflation. But what are you really paying for when you put $5-a-gallon gasoline in your (non-electric) vehicle? Crude oil, mostly. “A little more than half of the price of the gasoline relates to the price of crude oil,” University of Houston…