2 decades of right turns

This article is part of The Week‘s 20th anniversary section, looking back at how the world has changed since our first issue was published in April 2001.

Saint Paul considered himself an “apostle to the Gentiles” though he did not number among them, and it’s in this sense I’ve joked that, as a journalist, I’m an apostle to the American right.

That is, I don’t call myself a conservative, except temperamentally. I’m certainly not a Republican. Though I’ve recently had a few people dub me a centrist, my own label of choice is libertarian, and I make all the usual protests to my progressive friends that we libertarians are not properly located on the right wing of American politics.

But I did grow up there. I remember thinking it was vital George W. Bush win the 2000 election, and the presidential campaign where I interned eight years later was not within the Libertarian Party but a vehemently rebuffed libertarian incursion into the GOP. Much of my writing today is for or about the right. It’s still familiar territory — but it seems to grow less recognizable by the day.

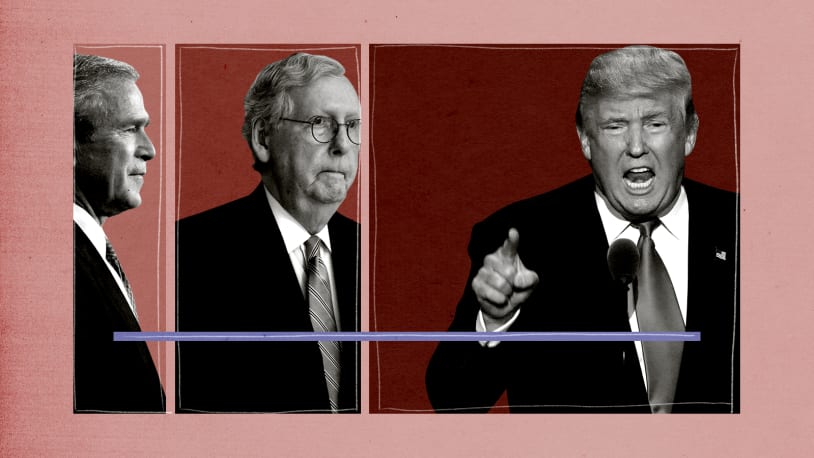

Over the past two decades, which correspond almost exactly to the post-9/11 era, the American right has changed remarkably. In 2001, Bush was president, the literal heir of the political heir of Ronald Reagan. He’d been elected talking about free markets and free trade, “compassionate conservatism,” and a “humble” foreign policy. Coming off the sexual scandals of the Clinton era, Republicans cast themselves as the party of virtue. The party of artless patriotism and family values. The party of principle, of grown-ups, of Mayberry and small farmers and Wall Street capitalists and country clubs. The party seated squarely on Reagan’s three-legged stool of fiscal conservatives, social conservatives, and defense hawks.

That is not the American right of 2021. Each leg of the stool has been thoroughly reshaped.

Perhaps most visible are the changes to the first leg, fiscal conservatism — a category I’ll broaden to include meta-level ideas about the size and scope of government; the legitimacy and value of state regulation and social welfare programs; and attitudes toward large corporations, international trade, and the market economy. Two decades ago, the right was still in thrall to the fusionist consensus, the partnership between conservatives and libertarians built on a then-shared vision of small government, at least where economic matters were concerned. To borrow the memorable phrasing of Grover Norquist of Americans for Tax Reform in 2001, the fusionist goal was not “to abolish government,” but to “reduce it to the size where I can drag it into the bathroom and drown it in the bathtub.”

The right no longer wants a drownable government. Republicans and libertarians are no longer, as Reagan argued in 1975, “traveling the same path,” because the median Republican is now more an economic populist than a fiscal conservative.

I’m painting in broad strokes here, I know, and there’s no denying that tax cuts still thrill the GOP heart or that Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) is still trying “to get as right-of-center an outcome as possible.” Nevertheless, the differences are stark. A YouGov survey of Republican voters earlier this year found nothing like the free-market orthodoxy of the past. Instead, these voters expressed wariness of foreign trade, with four in 10 saying they think it hurts the American economy and six in 10 affirming it harms our job market.

Gone as well is deep skepticism of “entitlements,” at least for certain favored demographics; now, two in three say “it’s more important to keep Social Security benefits at current levels even if it means raising payroll taxes.” A 2020 Public Agenda/USA TODAY/Ipsos poll found similar trends, reporting majority Republican support for state and federal job creation via infrastructure projects, incentives for domestic industry, and reduction of educational costs. Most Republican voters want to raise the minimum wage and increase regulation of tech companies.

“All the things that defined economic thinking before [former President Donald] Trump are now a complete split,” said Ethics and Public Policy Center senior fellow Henry Olsen, who managed the YouGov study. The late Rush Limbaugh agreed: “Nobody is a fiscal conservative anymore,” the radio host told a caller in 2019. “All this talk about concern for the deficit and the budget has been bogus for as long as it’s been around.” Spend away, Limbaugh argued, because “the great jaws of the deficit have not bitten off our heads and chewed them up and spit them out,” and perhaps they never will.

Even capitalism has lost its seat of honor, particularly as large corporations learn that touting progressive platitudes in glossy ads is a good way to get money — or boycotts by right-wing pundits and the Twitter trends and headlines they bring. “If the right wants [to push back on this ‘woke capitalism’],” contended a reader letter The American Conservative‘s Rod Dreher featured on his popular blog in May, “then it has to be prepared to inflict economic costs on big business, including antitrust action, regulation, support for big labor, ending tax breaks, and a whole host of issues. This is a complete anathema to the fusionist, business, and donor class of the party, but, if implemented, it would be highly effective.”

It would not be highly palatable to the conservative movement that was, but that movement is fading now. Fusionism is over, at least among those with real power. McConnell is labeling corporate political statements “economic blackmail” by a “woke parallel government.” The “libertarian moment” has passed in the GOP, some folk libertarian impulses notwithstanding, and I don’t expect the clock to tick toward it again in the foreseeable future. The right of today is entirely comfortable with a spendy, activist government, an indebted and mercantilist Washington that wields regulatory power for ideological ends.

Trump’s success with hardline immigration policies is symptomatic of this shift. In the early 2000s, there was a real diversity of opinions on immigration in the GOP. There were hardliners, yes, but also Republicans who took a more open approach, casting immigration reform as a matter of expanding the labor pool for American businesses, simplifying federal bureaucracy, and welcoming newcomers — many fleeing tyranny or persecution — to pursue their free-market dreams. The tenure of former Rep. Tom Tancredo (R-Colo.), who wanted to pause even legal immigration “until we no longer have to press one for English and two for any other language,” coincided with the Senate passage of the Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act of 2006, which included a path to citizenship for immigrants who had been in the country illegally for five years or longer. Though it never became law, the bill had Republican sponsors and strong bipartisan support.

When Elián González was taken from his family for deportation to Cuba in the final days of the Clinton administration, Rudy Giuliani (then the Republican mayor of New York City, since a close Trump ally) slammed the border control agents responsible. He called them “storm troopers using guns” to “rip a boy away from a family that is caring for him, and a boy who has at least indicated an interest in growing up in democracy and freedom.” And as recently as 2013, the “gang of eight” immigration reform effort, which also outlined a path to citizenship, counted Sens. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) and Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) among its numbers. Rubio has since repudiated the project and taken a more restrictive stance, and Graham made a similar move.

It no longer makes sense to speak of immigration as part of this first, fiscal leg of the stool. The modern GOP wants to dramatically expand the federal government where border security is concerned, and anyway, immigration policy is mostly culture war now. Fox News host Tucker Carlson, a skilled navigator of the flow of right-wing opinion, this past spring claimed “the Democratic Party is trying to replace the current electorate … [with] more obedient voters from the Third World.” He denied he was speaking of “a racial issue” or “white replacement theory” while yet decrying “change[s to] the population” which “dilute the political power” of people like him. Immigration in a discourse like that is better located in the second leg, where we turn to social issues.

The culture war didn’t begin in the last 20 years, of course, but its terms of engagement have changed. (Those changes aren’t exclusively attributable to the right — far from it — but given the focus of this article, that’s where my attention will be.) So much analysis of the right’s approach to social issues in the past five years has focused on white evangelicals and their relationship to Trump. That’s understandable, and I’ve written plenty on evangelicals myself, but it can also obscure another key phenomenon: the rise of the post-religious right.

Going to church didn’t stop people from voting for Trump. On the contrary, among professing Christian voters, higher church attendance generally correlated with more Trump votes in 2020. But fewer and fewer people are involved in houses of worship. Membership rates for churches, synagogues, and mosques held roughly steady, between 70 and 75 percent, from before World War II until the new millennium began. Over these past two decades, it plummeted and is now below half for the first time on record.

And here’s the thing: Going to church may make a Trump vote more likely, but it’s a vote that comes from a different set of beliefs than a Trump vote cast by a member of the irreligious right. Polling has found the “more often a Trump voter attended church, the less white-identitarian they appeared, the more they expressed favorable views of racial minorities, and the less they agreed with populist arguments on trade and immigration,” wrote The New York Times‘ conservative columnist, Ross Douthat, in 2018. The differences were particularly sharp on matters of race and racism, Douthat observed, with “[s]ecularized Trump voters” pairing “an inchoate economic populism with strong racial resentments.” Unchurched Republicans were nearly three times as likely as churchgoers to say their whiteness is “very important” to their identity.

It may be tempting for those outside the right to dismiss this evolution as irrelevant if the presidential votes are the same regardless. That would be a mistake. As French conservative Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry wrote for The Week in 2017, “[i]f you didn’t like the Christian right, you’ll really hate the post-Christian right,” because “the Christian gospel’s relentless focus on the intrinsic dignity of every human being, and on Christ’s focus on the outcast and the outsider, at least can put a brake” on racism and other types of identitarianism.

As the right secularizes, that constraint is fading. A post-religious right has no reason to attempt to see inherent worth in its political opponents. It needn’t have “opponents,” in fact, just enemies. It can shrug at “s–thole countries” and “grab ’em by the pussy” and anything cruel or foul or even illegal as long as the other side is on the receiving end, because winning is what matters. All is transactional. All is consequentialist. Own the libs. Claim the power. Revel in the thrill. (A headline at American Greatness, entirely sincere: “I won’t take the [COVID-19] vaccine because it makes liberals mad.”)

The trend I’m describing here is not universalized on the right, and it doesn’t necessarily alter Republican policy preferences (immigration is a notable exception), just as it didn’t necessarily alter voters’ decisions about Trump. On familiar culture war fronts, like abortion, LGBTQ issues, and religious liberty, the right-wing position since 2001 has stayed fairly consistent or — on gay marriage — moved left. But the tenor is different. It’s more tribal, less principled. Less about deeply held religious conviction and more about cosseting fears, indulging anger, and punishing the out-group. “Recent party polling indicates that, more than any issue, Republican voters crave candidates who ‘won’t back down in a fight with the Democrats,'” The New York Times reported this year.

It turns out “secularization isn’t easing political conflict,” The Atlantic‘s Peter Beinart has written. “It’s making American politics even more convulsive and zero-sum.” As religiosity declines, the American right is growing more utilitarian, more openly rude, reactionary, and racist.

Last, we come to foreign policy, the stool’s third leg. After the 9/11 attacks, Bush promptly dropped all that humility stuff and decided it actually was “the role of the United States is to go around the world and say, ‘this is the way it’s got to be.'” Neoconservatism was ascendant, and the United States invaded Afghanistan, then Iraq, and embarked on doomed projects of regime change, nation-building, and regional transformation.

Many of those military misadventures are still underway in some form, but the most recent Republican president won, in part, because of his explicit condemnation of their beginning. Trump’s supporters cast him as a foreign policy renegade, a strong innovator who could end endless wars and achieve new diplomatic triumphs through his unparalleled deal-making prowess. They touted “his ability to identify America’s national interest clearly and pursue it without regard to outdated ideological investments.”

It’s true Trump wasn’t concerned with outdated ideological investments, but only because he — and so much of the American right today — has little in the way of ideological investments in foreign policy at all. Neoconservative foreign policy was horrific, but it had an internal logic. The Jacksonian mood of GOP foreign policy today, by contrast, is impulsive and incoherent. It decries permanent warfare but is not opposed to war in any principled sense.

Indeed, Trump never actually ended a war, and he blew up more major diplomatic accords than he engineered. Once-promising overtures to North Korea were wasted. The Iran nuclear deal withdrawal was borne of ridiculous hubris. Perhaps the most important pact of Trump’s presidency, the U.S.-brokered deal between Israel and the United Arab Emirates, does not directly concern the United States. His foreign policy decisions sometimes seemed to be determined by whether he’d had more fun golfing with the Republican lawmaker arguing for military action or the one arguing against it.

Here’s the crux of the matter: Suppose another 9/11-style attack happened in the United States and, in the aftermath, we learned the perpetrators had a host country arrangement like that of al Qaeda with the Taliban in Afghanistan. We have 20 years of hindsight. We know how costly, counterproductive, and tragic the war in Afghanistan was. We know it was the start of a whole slate of regional wars and smaller military interventions in Iraq, Syria, Libya, Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia, and elsewhere. We know the futility displayed in its conclusion.

Yet for all that knowledge, my belief is that if another GOP president pushed for war in the wake of our hypothetical terrorist attack, most of the right would be raring to go. That includes many Trump supporters who liked his criticism of Bush-era foreign policy. They’re not antiwar so much as tired of these wars — and eager to redirect attention and resources to economic populism and culture wars at home.

Likewise inconsistent is the new right’s attitude toward the intelligence establishment and law enforcement more generally. On the one hand, the GOP that passed the Patriot Act is not the GOP of today, in which conspiracy theories about the “deep state” cast suspicion on the CIA, NSA, FBI — even the FDA. Trump’s rhetoric toward these agencies was often antagonistic, and when the former president’s fans stormed the Capitol Building in January, they attacked police defending the complex, seriously injuring many officers and possibly contributing to one’s death.

On the other hand, that same rioting crowd at the Capitol had “Blue Lives Matter” flags. Respect for the military and law enforcement remains strong in a milieu where patriotic correctness flourishes. For the patriotically correct, “[b]elieving in American exceptionalism means that anything less than chest-thumping jingoism is capitulation,” wrote the Cato Institute’s Alex Nowrasteh at The Washington Post. In this perspective, Nowrasteh continued, “[u]nionized public employees who can’t be fired are bad at their jobs and are more interested in increasing their own power than fulfilling their public duties, except if they are police or Border Patrol officers, who are unselfishly devoted to their jobs.” (Giuliani’s “storm troopers” line would never publicly pass Republican lips today, and not only because of swings on immigration.)

To be clear, I’m glad of some of the policy outcomes newly complicated Republican views on law enforcement have produced, like the First Step Act and the permitted lapse of certain features of the Patriot Act in March of 2020. Yet where protection of privacy, in particular, is concerned, I don’t see burgeoning civil libertarianism so much as self-protection. Trump didn’t want to rein in the FISA court because it had rubberstamped tens of thousands of surveillance requests, rejecting a mere 11 of nearly 34,000 between 1979 and 2013. No, his objection was its approval of surveillance of his campaign. The broader incongruity of right-wing attitudes here similarly pairs, by some measures, some decline in authoritarianism with a spike in tribalism and paranoia.

Beyond all these shifts in policy and philosophy, maybe the biggest evolution of the American right over the past 20 years is the decline of the conservative temperament.

Conservatism, as it was once understood, is “not an ideology or a creed,” David Brooks explained at The New York Times in 2007, “but a disposition, a reverence for tradition, a suspicion of radical change.”

In this sense, conservatism is marked by prudence and restraint. It cultivates institutional stability and regard for the wisdom of the past. It preaches a modest patriotism, not the bombast of patriotic correctness, and abhors gaudiness, indecency, and waste. “Temperamental conservatism understands that in order to preserve anything, it must be kept within certain limits,” wrote Daniel Larison for The American Conservative. “It recognizes that resources are finite and can be exhausted by current generations at the expense of posterity.”

This is a conservatism with which I can identify. It is also a conservatism dangerously dwindled on the American right.

No longer is temperamental conservatism in healthy tension with progressivism’s constant forward push. Rather, as Wall Street Journal columnist Peggy Noonan wrote of Sens. Josh Hawley (R-Mo.) and Ted Cruz (R-Texas) the day after the Jan. 6 Capitol sedition, too much of the right today is “like people who know the value of nothing, who see no frailty around them, who inherited a great deal — an estate built by the work and wealth of others — and feel no responsibility for maintaining the foundation because pop gave them a strong house, right? They are careless inheritors of a nation, an institution, a party that previous generations built at some cost.”

Instead of prudence, profligacy. Instead of serious politics, entertainment. Instead of virtue, victory. The change is so significant I’m rarely willing to use the word “conservative” to talk about the American right, because so little of it is conservative at all.

This article is part of The Week‘s 20th anniversary section, looking back at how the world has changed since our first issue was published in April 2001. Saint Paul considered himself an “apostle to the Gentiles” though he did not number among them, and it’s in this sense I’ve joked that, as a journalist, I’m…

This article is part of The Week‘s 20th anniversary section, looking back at how the world has changed since our first issue was published in April 2001. Saint Paul considered himself an “apostle to the Gentiles” though he did not number among them, and it’s in this sense I’ve joked that, as a journalist, I’m…